Cautiously, each of Lahiri’s characters patches together their own identity, making this resonant fable neither uniquely Asian nor uniquely American, but tenderly, wryly human.

What is it like to have a really weird name? Quite frustrating. But how is it like to live in a foreign land and see your children merge in the local culture than your tradition? Probably equally frustrating.

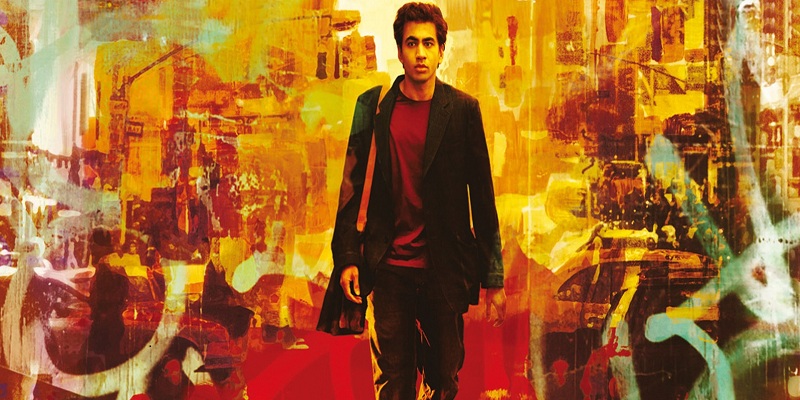

Jhumpa Lahiri’s gracious novel, The Namesake, is her first full length work. Lahiri made her debut with The Interpreter of Maladies, a Pulitzer Prize-winning short-story collection, peopled by Asians whose work or study took them to the US. In refined, empathetic prose, she chronicled the stresses and strains of integration and assimilation, and The Namesake covers similar ground.

The novel begins in Calcutta and then skips 8,000 miles across the water to suburban America. The story is about three decades in foreign land. The story runs along the Russian writer Nikolai Gogol in the beginning, through a chunk of its middle and in the end.

United in a Bengali arranged marriage, Ashima and Ashoke Ganguli fid themselves in wintry Boston where he studies for a PhD at MIT and she navigates her loneliness. When Ashima becomes pregnant, her grandmother writes letter with names – one for a boy and one for a girl. But the letter is lost in the post and American bureaucracy overtakes tradition.

Forced to pick a name for baby boy Ganguli’s birth certificate, Ashoke lights on Gogol, whose stories once saved his life, keeping him up reading as his night train hurtled towards disaster, and ensuring that he was one of the few to be pulled alive from its wreckage.

Gogol Ganguli finds his name ‘simple, impossible, absurd’. According to Bengali custom, he is given a ‘good name’ too – Nikhil – but he adopts it only with his first kiss, thereafter feeling as if ‘an errata slip were perpetually pinned to his chest’.

In time, these vague sentiments harden into a rueful sense of filial disloyalty. ‘Living with a pet name and a good name, in a place where such distinctions do not exist,’ he sighs. ‘Surely that was emblematic of the greatest confusion of all.’

And yet this is not a lament for lost cultural identity – Lahiri is too honest an observer for that, and Ashima and Ashoke’s feelings for the country and culture in which they’ve made their home are convincingly complex.

‘Being a foreigner,’ Ashima decides early on, ‘is a sort of lifelong pregnancy – a perpetual wait, a constant burden, a continuous feeling out of sorts’, but as Gogol and his sister teach her the ‘rules’ of Christmas and throw hot dogs and cheese slices into the supermarket trolley, her sadness for her forsaken former life is intermingled with pride and gratitude for the new.

Cautiously, each of Lahiri’s characters patches together their own identity, making this resonant fable neither uniquely Asian nor uniquely American, but tenderly, wryly human.